76

ICELAND

12

Wanderschäfer

1

Home in the Heather

6

analogue summer

18

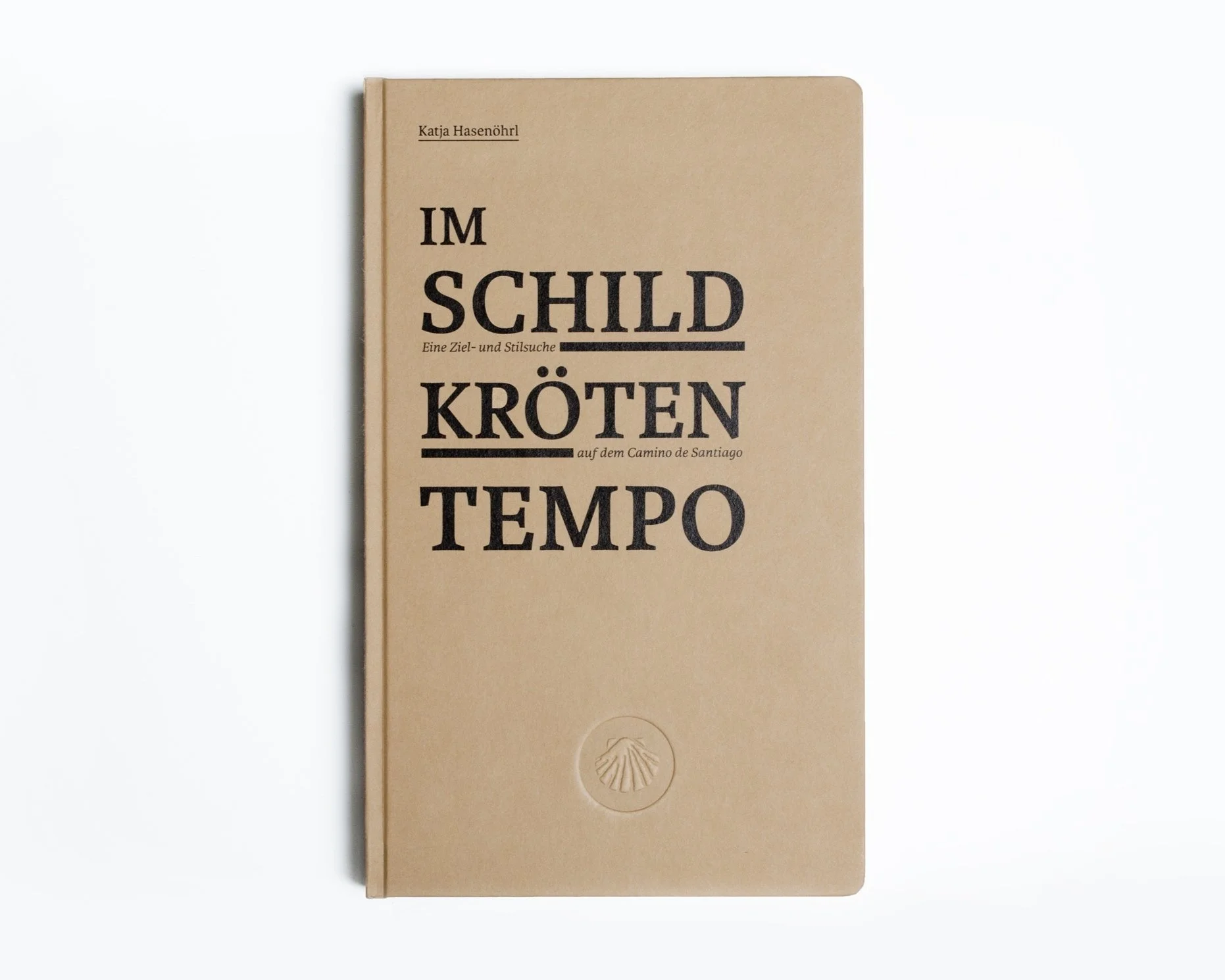

Im Schildkrötentempo

5

Where are you going?

8

Queens of Vienna

59

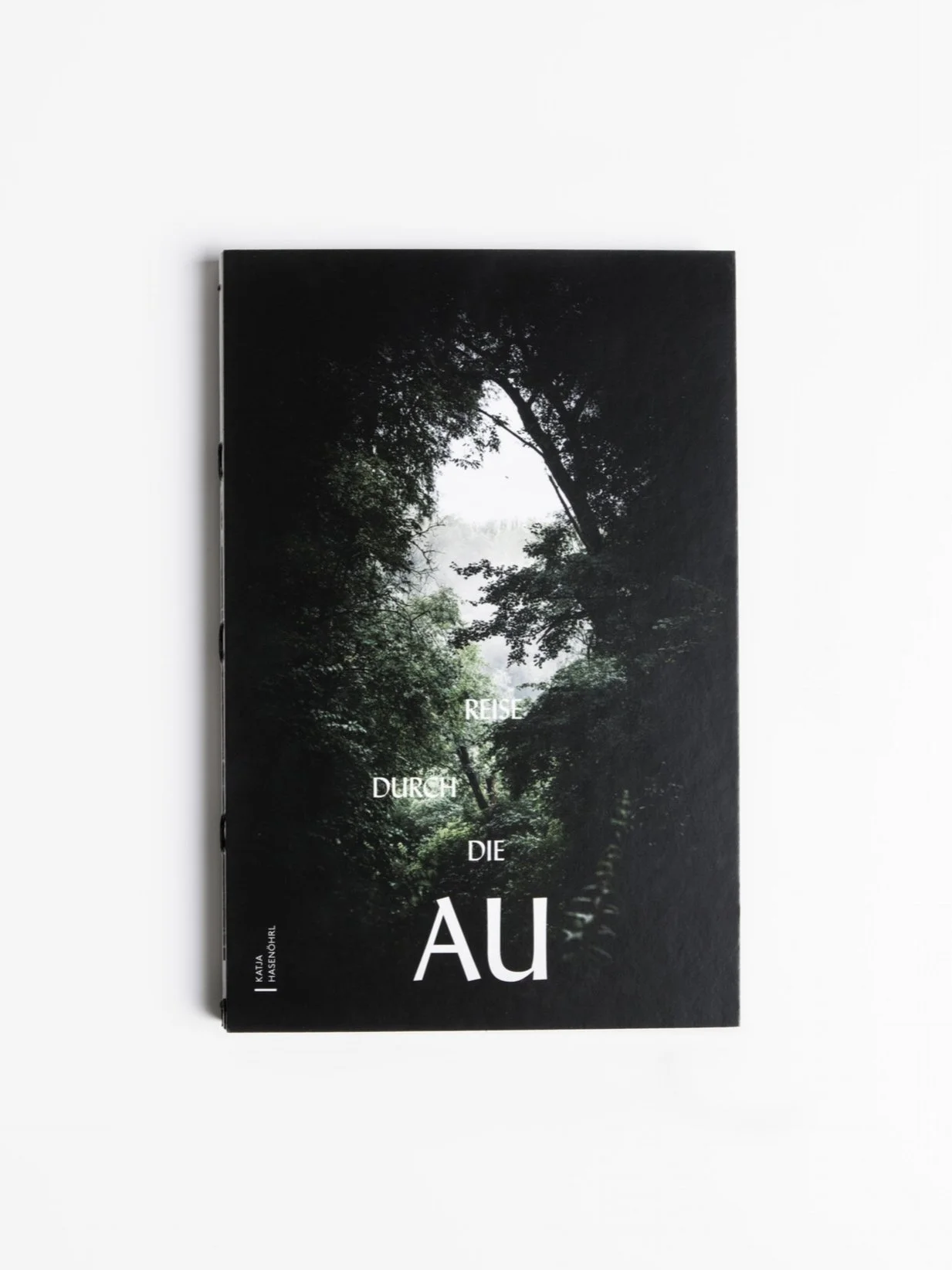

Reise durch die Au

13

Réttir

9

ILLUSTRATIONS

55

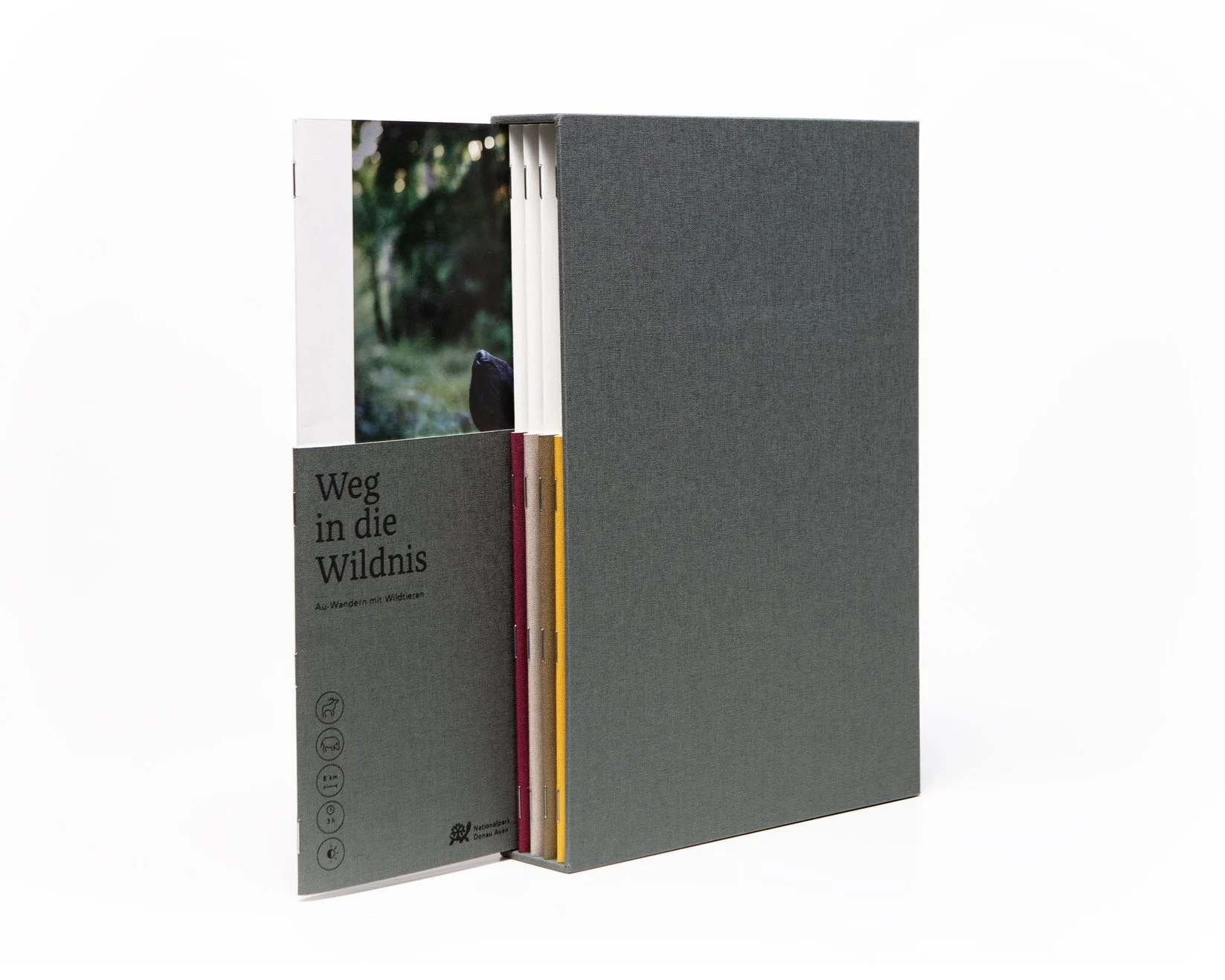

Au Wege

10

Takashi Homma

19

Kuratorium Wald × Generali

7

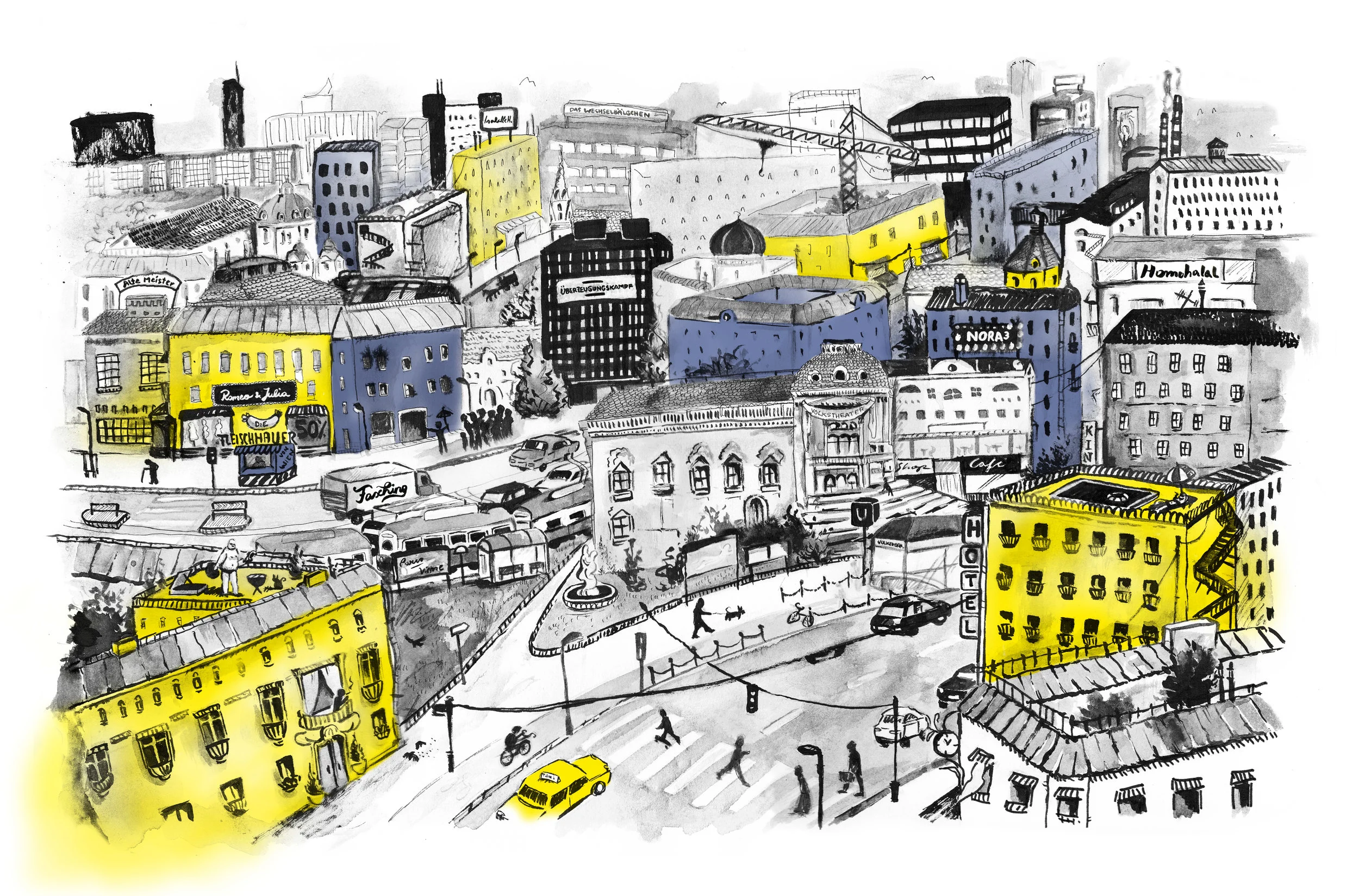

Volkstheater Wien

5

Portrait

11

Racing against her own time

10

How to save water

4

Circus Piccolo

33

Scheucher Winery

40

Human Rights Space

15

mypoppies

25

ONpoint magazine

0

LOGOS

8

UNESCO Austria

7

Positive Aging

12

Tales of Narwhales

12

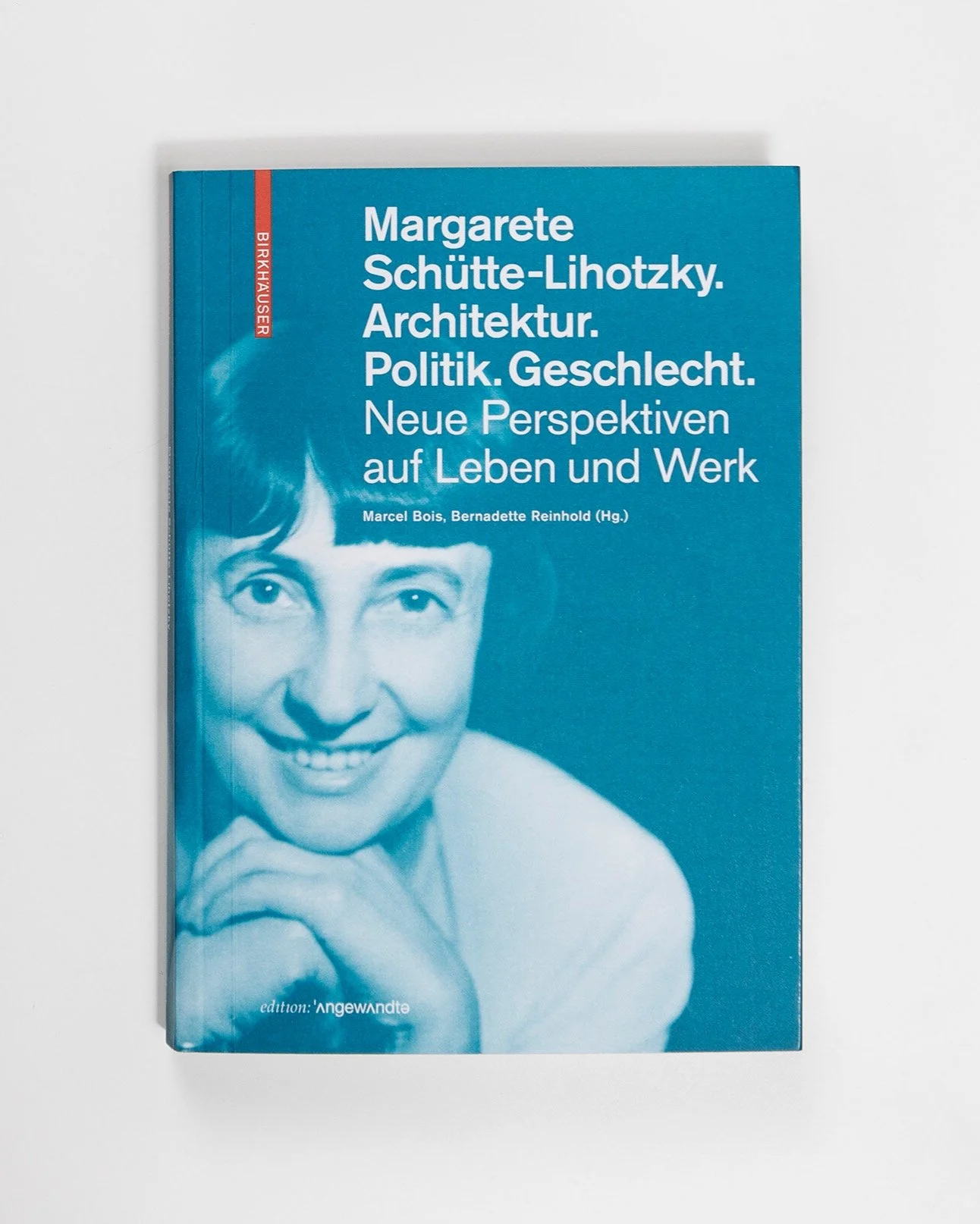

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky

21

OPEN HOUSE

12

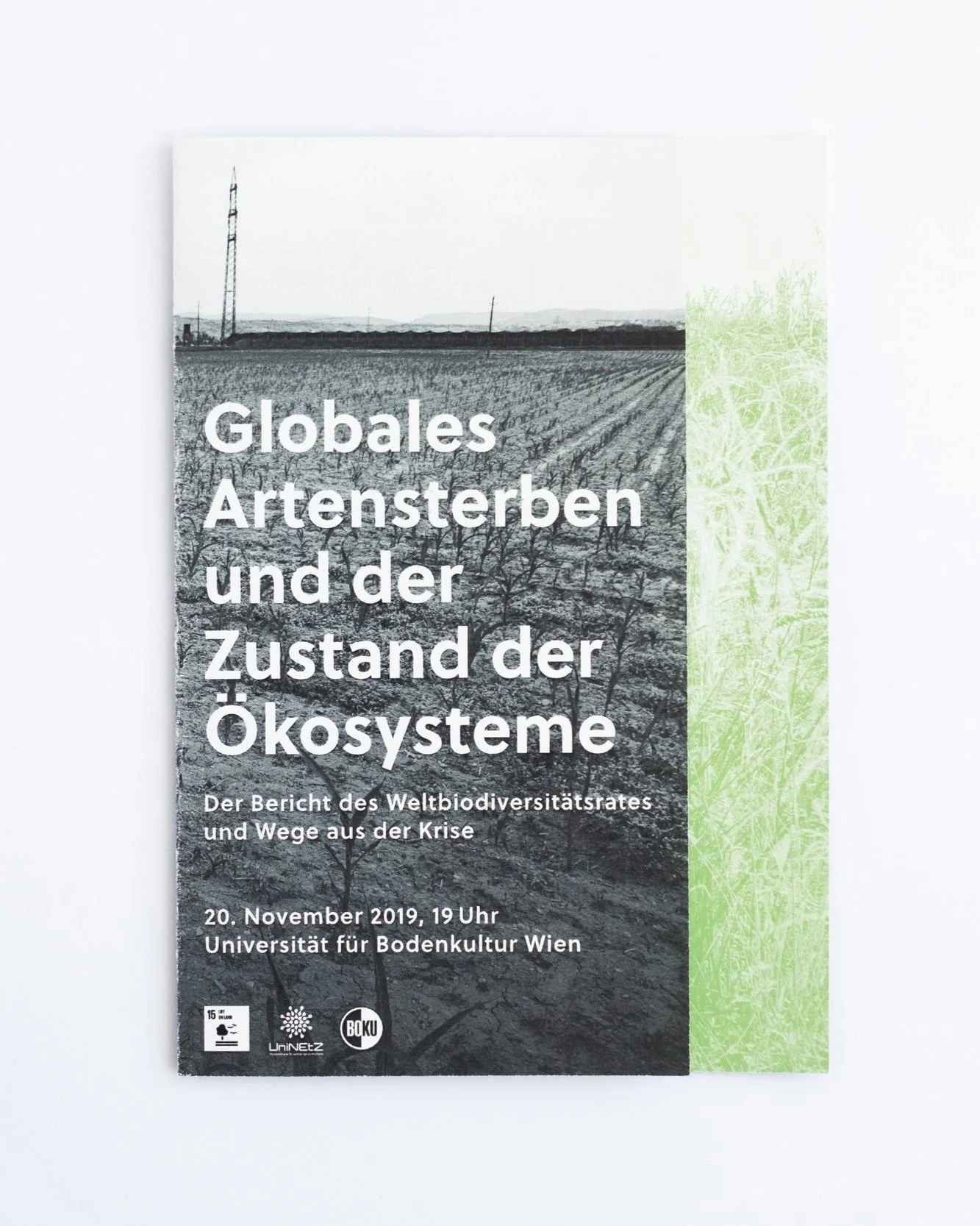

BOKU

9

Margarethe Schütte-Lihotzky

12

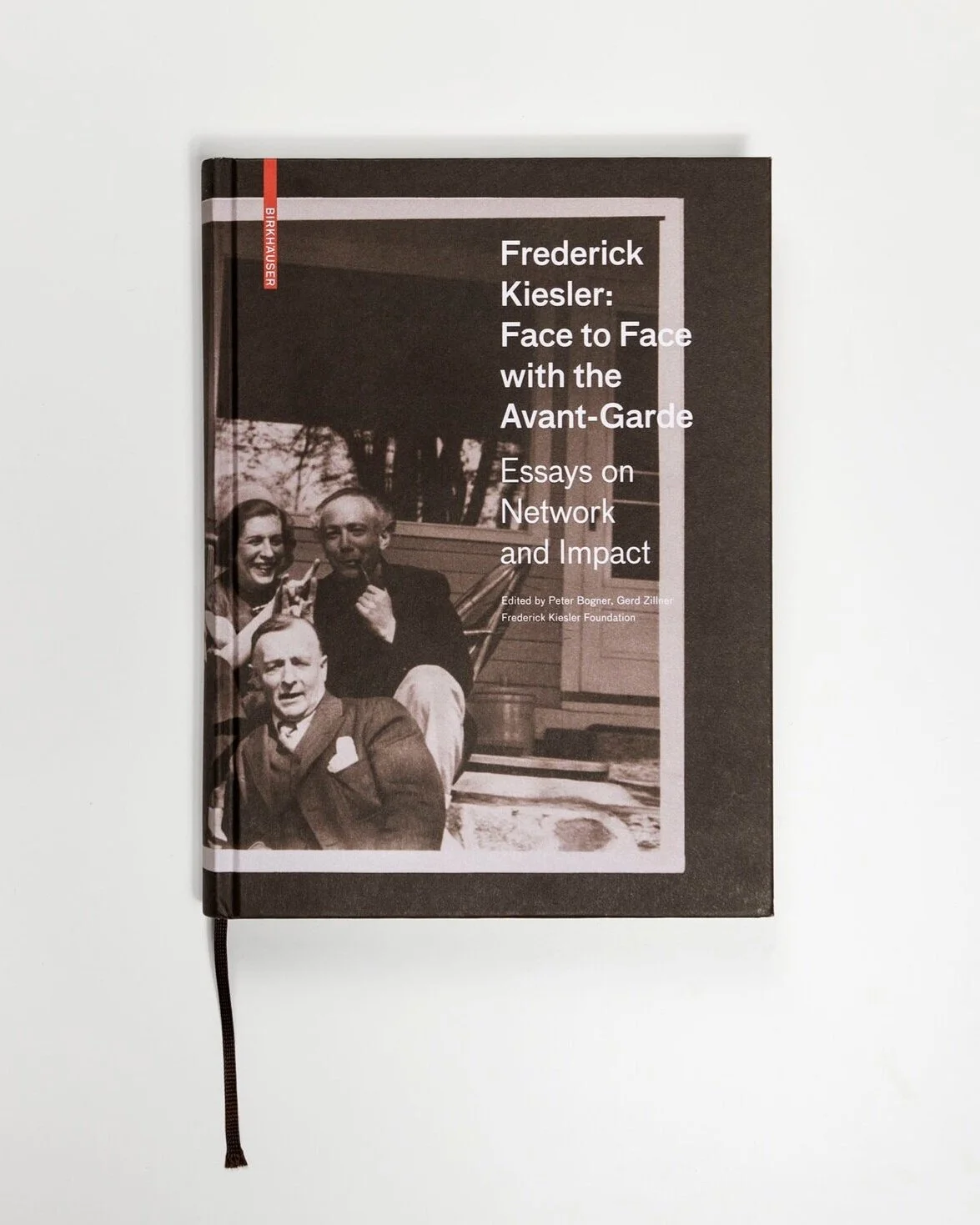

Frederick Kiesler: Face to Face with the Avant Garde

5

University of Applied Arts Vienna Folder

9

Powernapping

10

Society Now!

10

Biennale Sessions

1

Russian Circus

0

Neue/-r/-s Gallery